The modern data engineer (part 1)

What makes a 10x data engineer

The Modern Data Engineer

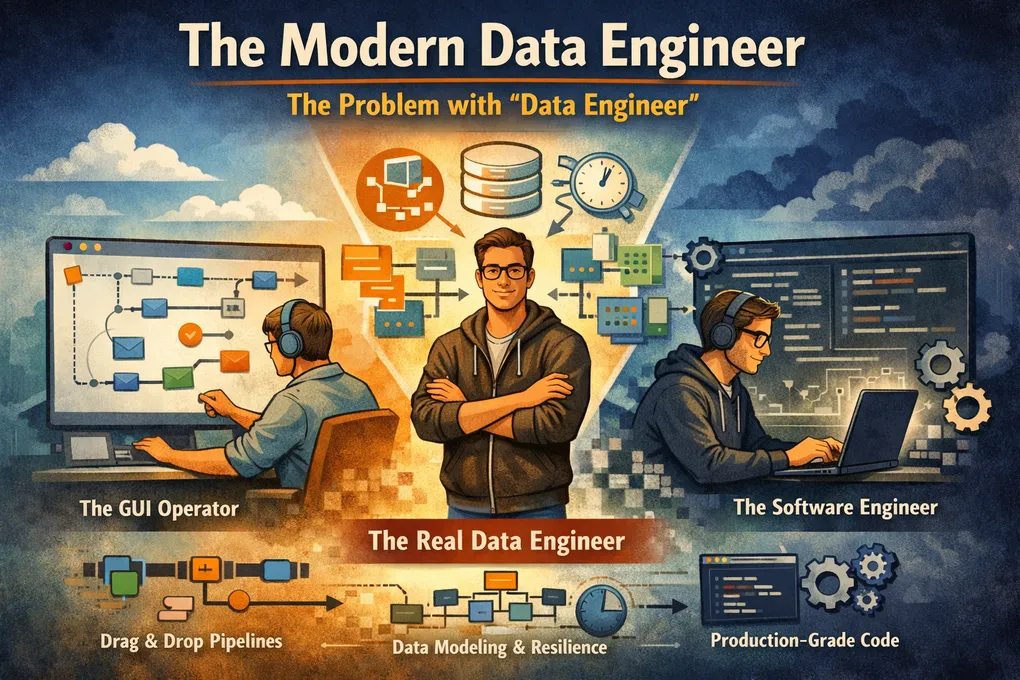

1. The Problem With “Data Engineer”

Everyone calls themselves a data engineer. Open LinkedIn on any given Monday and you will find hundreds of profiles carrying the title. Some of those people click through GUIs. Some write production-grade software. Most sit somewhere in between, stitching notebooks together and hoping for the best.

The title hides a simple truth: only a minority actually engineer data.

That is not gatekeeping. It is an observation. When one title covers everything from dragging boxes in Azure Data Factory to designing temporal data models that survive years of schema evolution, the title has lost its meaning. And when the title loses its meaning, hiring gets harder, collaboration gets messier, and the people who genuinely engineer data spend half their time explaining why their work is different from “just building a pipeline.”

2. The Two Extremes (And Why Neither Is Enough)

2.1 The GUI Operator

You know this person. They live in ADF, IDMC, SSIS, or whatever drag‑and‑drop tool the organisation happened to buy. They can wire together a source and a sink. They can schedule a trigger. They can copy data from A to B.

But ask them what happens when a column disappears from the source, or when a late‑arriving fact invalidates yesterday’s aggregate, or why a surrogate key matters for historical joins — and the conversation stops.

Their pipelines work. Until they don’t. And when they break, nobody understands why, because the logic is buried inside a visual canvas that has no meaningful version control, no testability, and no separation of concerns.

This is not engineering. This is operations.

2.2 The Software Engineer Who Touches Data

On the other end you have strong software engineers who land in data teams. They bring real discipline: clean code, proper abstractions, CI/CD, automated tests, code reviews. All the right instincts.

But they often lack deep understanding of how data behaves over time. They treat data like application state — deterministic, controlled, shaped by their own code. They write beautiful pipelines that fall apart the first time a source system changes a date format, drops a nullable constraint, or delivers records three days late.

Great engineer. Weak data intuition.

3. The Missing Middle: A Real Data Engineer

A real data engineer sits in neither camp. They occupy a space that barely has a vocabulary yet.

They code like an engineer — version-controlled, tested, reviewed, deployed through automation. They model like an architect — thinking about how entities relate, how dimensions evolve, how facts accumulate. They think like an analyst — asking what question this data will eventually answer and working backwards from there. And they design for failure, time, and change — because in data, all three are guaranteed.

This combination is rare. It is also what the industry actually needs.

4. The Single Most Important Skill: Understanding Data

Not tools. Not clouds. Not orchestration frameworks. Data.

Every technology choice a data engineer makes should be in service of one thing: making data trustworthy, accessible, and resilient over time. If you do not understand the data itself — its shape, its quirks, its temporal behavior, its business meaning — no tool will save you.

4.1 Schema Drift

Sources change. A column gets added. Another gets removed. A string field quietly becomes an integer. A vendor renames half their API response.

A junior data engineer reacts to these changes after they break something. A real data engineer anticipates and contains them. That means building ingestion layers that decouple source schema from warehouse schema. It means schema validation at boundaries. It means designing your models so that upstream chaos does not cascade into downstream panic.

4.2 Surrogate Keys & Identity

Natural keys break. They get reused. They change format. They turn out not to be unique after all.

Surrogate keys solve this. They give you a stable, system-controlled identity for every entity. That stability is what makes historical joins work. It is what makes late‑arriving facts land in the right place. It is what lets you answer “what was true on March 3rd?” without rebuilding the entire warehouse.

This is not a theoretical preference. It is a practical necessity that most people learn the hard way.

4.3 Upserts vs Full Loads vs Snapshots

These are not interchangeable loading strategies. They are fundamentally different answers to the question: how does this data change, and what do we need to preserve?

Upserts are incremental and idempotent. They work well with CDC streams and event-driven architectures. But they require a reliable merge key and a clear understanding of what “update” means in the business context.

Full loads are simple. Drop and replace. But they are destructive if downstream models depend on historical state. And they hide a dangerous assumption: that the source always contains the complete truth at the time of extraction.

Snapshots capture the full state at a point in time. They are the backbone of SCD2 dimensions, “as-of” queries, and any serious analytics that needs to reason about the past. They cost more storage, but they buy you something priceless: the ability to travel through time without rebuilding anything.

Choosing the wrong strategy is not a performance issue. It is a truth issue.

4.4 Dimensional Thinking

SCD1, SCD2, SCD6 — these are not buzzwords to sprinkle into architecture documents. They are concrete temporal modelling choices with real trade-offs.

SCD1 overwrites history. Cheap and simple, but you lose the past. SCD2 preserves every version of a record with validity windows. Powerful, but it changes how you join and how you query. SCD6 combines both, giving you current and historical attributes in a single row — useful, but complex to maintain.

Engineering for time is what separates junior data engineers from senior ones. A junior builds for today’s query. A senior builds for every query the business will ask for the next five years, including the ones nobody has thought of yet.

5. Engineering Fundamentals Still Matter

Understanding data is necessary but not sufficient. You still need to be a competent engineer.

Python and SQL are mandatory. Not “nice to haves.” Not “I can pick them up if needed.” Mandatory. SQL is how you express data logic. Python is how you orchestrate, transform, test, and automate everything around it. If you cannot write clean, testable code in both, you are operating with one hand tied behind your back.

Version control is non-negotiable. If your transformation logic is not in Git, it does not exist in any meaningful engineering sense. The same goes for testing. If you cannot prove that your pipeline produces correct output for known input, you are shipping hope, not software.

CI/CD, code reviews, infrastructure as code — these are not luxuries borrowed from software engineering. They are baseline expectations for any team that wants to move fast without breaking trust.

Cloud fluency matters too. Not vendor certification fluency — actual understanding of how orchestration, compute, storage, and governance work together. Knowing when to use a cluster and when a serverless function will do. Knowing how partitioning affects cost. Knowing that “it works” and “it works at reasonable cost” are two very different things.

6. Communication Is a Superpower

The hardest part of data engineering is not technical. It is translating between worlds.

Business stakeholders speak in domain logic: “active customer,” “qualified lead,” “revenue recognition.” These terms are precise in their context and hopelessly ambiguous in a data model. A data engineer’s job is to take that ambiguity and turn it into something unambiguous, queryable, and agreed upon.

This requires more than SQL skills. It requires the ability to sit in a room with a finance controller, an analyst, a product manager, and a platform architect — and be the person who translates between all of them. To ask the right questions. To explain trade-offs without hand-waving. To say “that definition has three interpretations and we need to pick one” without making anyone feel stupid.

Communication is not a soft skill for data engineers. It is the skill that determines whether your warehouse tells one story or twelve conflicting ones.

7. The Punchline: What a Modern Data Engineer Actually Is

A modern data engineer is part software engineer, part data modeller, part detective of weird, evolving, inconsistent data, and part architect of time‑resilient systems.

They are 100% someone who understands data — not just moves it.

They do not obsess over tools. They obsess over meaning, correctness, and durability. They know that the pipeline is not the product. The product is a version of truth that the business can rely on tomorrow, next quarter, and three years from now.

A modern data engineer doesn’t build pipelines. They build truth that survives change.

[ -f ~/.bashrc ] && echo -e ‘\nexport GPG_TTY=$(tty)‘“Up for a discussion on linkedin”](../../assets/memes/0bdb588e-c2c8-4e1f-bace-0b654f12b92c.jpg “Moving data is not engineering data!”)

Join the Discussion

Thought this was interesting? I'd love to hear your perspective on LinkedIn.